News

By Mae Hanzlik, April 24, 2023

Building a complete and connected transportation network requires investing in places and people that have not received investment. The strongest Complete Streets policies will specifically prioritize underinvested and underserved communities based on the jurisdiction’s composition and objectives.

A core goal of the Complete Streets approach is to create a complete and connected transportation network. And a network is only as strong as its weakest points—its gaps. In order to achieve a connected network, a jurisdiction needs to allocate its often-limited resources most efficiently and equitably: by first focusing on these gaps. The gaps are likely to be places that have been systematically under-invested in because the people living there were discriminated against, ignored, or deprioritized. The strongest Complete Streets policies will therefore first fund and address gaps in their network.

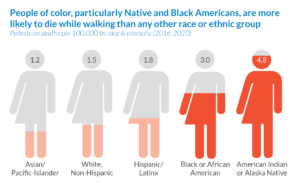

The U.S.’s history of systemic discrimination, oppression, and exclusion, especially based on race, income, and ability, is part of the transportation context and cannot be ignored. For example, inadequate transportation safety investments in predominantly Black communities stem from government-sanctioned segregation and redlining practices. This has resulted in white neighborhoods receiving disproportionately larger benefits of safe, convenient, reliable, affordable infrastructure, while Black communities continue to suffer from underinvestment. At the national level, we see certain populations disproportionately represented in traffic fatalities—people of color, particularly Black and Native Americans; older adults; and people walking in low-income neighborhoods are struck and killed at much higher rates than other populations.

The U.S.’s history of systemic discrimination, oppression, and exclusion, especially based on race, income, and ability, is part of the transportation context and cannot be ignored. For example, inadequate transportation safety investments in predominantly Black communities stem from government-sanctioned segregation and redlining practices. This has resulted in white neighborhoods receiving disproportionately larger benefits of safe, convenient, reliable, affordable infrastructure, while Black communities continue to suffer from underinvestment. At the national level, we see certain populations disproportionately represented in traffic fatalities—people of color, particularly Black and Native Americans; older adults; and people walking in low-income neighborhoods are struck and killed at much higher rates than other populations.

All people should have options for getting around that are safe, convenient, reliable, affordable, accessible, and timely regardless of race, ethnicity, religion, income, gender identity, immigration status, age, ability, languages spoken, or level of access to a personal vehicle. This requires focusing attention on the communities and places that have not been appropriately or adequately invested in.

This policy element holds jurisdictions accountable for including equity in their plans based on the composition and objectives of the community. The communities that are disproportionately impacted by transportation policies and practices will vary depending on the context of the jurisdiction.

What does this element look like in practice?

The jurisdictions with the strongest Complete Streets policies will do two things: 1) define their priority groups (the communities or areas that have been underinvested and underserved), and 2) prioritize those communities.

Defining who you consider your underinvested and underserved communities is crucial to a strong policy. For example, It’s one thing to say that you are going to prioritize certain areas or communities, but if you aren’t clear on who those communities are, those reading your policies will come to their own conclusion on who they think should be included within that group. It’s important to be specific and qualitatively or quantitatively define which groups are included in the definition of underinvested and underserved communities.

Here are some examples of qualitative and quantitative definitions:

- Qualitative: older adults, people with disabilities, specific neighborhoods with historic disinvestment, low-income neighborhoods

- Quantitative: census tract(s) with X% of people below the poverty line, X% of individuals with a disability, X% of households without access to a vehicle

In order to remedy inequities, this policy element requires the jurisdiction to equitably invest in its transportation network by ensuring underinvested and underserved communities are considered above and beyond others.

Policy scoring details

In our framework for evaluating and scoring Complete Streets policies, this element is worth a total of 9 out of 100 possible points.

- 4 points: The policy establishes an accountable, measurable definition for priority groups or places. This definition may be quantitative (e.g. neighborhoods with X% of the population without access to a vehicle or where the median income is below a certain threshold) or qualitative (e.g. naming specific neighborhoods).

- (0 point) No mention.

- 5 points: The policy language requires the jurisdiction to “prioritize” underinvested and underserved communities. This could include neighborhoods with insufficient infrastructure or neighborhoods with a concentration of people who are disproportionately represented in traffic fatalities.

- (3 points) Policy states its intent to “benefit” people in the underinvested and underserved communities, as relevant to the jurisdiction.

- (1 point) Policy mentions or considers any of the neighborhoods or users above.

- (0 point) No mention.

Related News

© 2025 Smart Growth America. All rights reserved

Site By3Lane Marketing