News

By Smart Growth America, July 15, 2019

Durham’s demonstration project on West Club Boulevard introduced a new, much-needed mid-block crossing between a major bus stop and a shopping mall. The project also closed a lane of traffic to create a space for buses to pull over and to encourage drivers to slow down and yield to people crossing.

Durham’s demonstration project on West Club Boulevard introduced a new, much-needed mid-block crossing between a major bus stop and a shopping mall. The project also closed a lane of traffic to create a space for buses to pull over and to encourage drivers to slow down and yield to people crossing.

Through the Safe Streets, Smart Cities Academy, Smart Growth America worked with three cities around the country, including Durham, to implement temporary safety demonstration projects. The City of Durham recognized their demonstration project as an opportunity to try out more intensive, inclusive methods of community engagement to reach segments of their community they have not connected with in the past. They identified a dangerous site along West Club Boulevard, where a frequently used bus stop across from a shopping mall offered no safe, convenient way for bus riders to cross. The team conducted intercept surveys at the bus stop to learn more about the safety challenges people experienced and to guide the design of their demonstration project. Based on these insights, the team reduced the number of lanes on West Club Boulevard and installed a new mid-block crossing, resulting in safer, slower driving speeds and better yielding to people crossing. The project also spurred important conversations and partnerships with bus riders and with a local bike advocacy group.

The bus stop on West Club Boulevard at Dollar Avenue is one of the top 20 most frequently used in the city, with approximately 150 boardings every weekday, predominantly by African American people, people who do not own a car, and people who make less than $25,000 per year. Immediately across West Club Boulevard, the Northgate shopping mall is a frequent destination for bus riders. In addition to the shops inside, the mall hosts a maker space, a farmers market, and various festivals. Following a recent transfer of ownership, Northgate will soon boast a health clinic among other community amenities.

Unfortunately, there was no safe, accessible, convenient place for people to cross between this well-used bus stop and the mall. People using wheelchairs or other mobility devices especially needed to go out of their way to cross the street. Drivers frequently sped along this four-lane road, and in just eight years, two people biking and six people walking were struck and injured near the site. A team from the City of Durham decided to work closely with the community, especially with people who ride the bus, to implement a safety demonstration project on West Club Boulevard.

Engaging the community

West Club Boulevard bridges two very distinct neighborhoods. Trinity Park to the east is a predominantly white, wealthier place whose residents proactively share their input with the city via social media and online surveys. To the west, Walltown is more racially and ethnically diverse and has a broader mix of income levels. These latter groups experience higher rates of traffic crashes in Durham, as well as across the nation as a whole, so their insights are especially important to guide safety projects. Unfortunately, the city has had difficulty engaging this community through online methods and traditional public meetings in the past. They recognized their demonstration project as an opportunity to set a new precedent for inclusive community engagement and to form new connections and partnerships with people who ride the bus.

“It’s very clear what happens with traffic fatalities and traffic injuries is they are inequitably distributed.”

—Mayor Steve Schewel, City of Durham

Between 2007 and 2015, eight crashes occurred on the segment of West Club Boulevard where the Durham team staged their demonstration project, including six crashes involving people waking (marked in green) an two involving people biking (marked in pink).

Between 2007 and 2015, eight crashes occurred on the segment of West Club Boulevard where the Durham team staged their demonstration project, including six crashes involving people waking (marked in green) an two involving people biking (marked in pink).

The team from Durham realized they needed to go beyond their typical online engagement and public meetingm model to make sure Walltown residents and people who ride the bus had a voice in guiding their demonstration project. In addition to collecting input through online surveys, they conducted in-person intercept surveys, where they spoke with people waiting at the bus stop who use the street on a day-to-day basis about the problems they were experiencing and the changes they would like to see. They also spread the word about their project through local media sources and staged pop-up meetings at nearby community events including a neighborhood association meeting, the Northgate Children’s Festival, and the Earth Day Festival.

The Durham team spent some time at the bus stop on West Club Boulevard observing how people cross the street and talking to bus riders about their experiences before and after making changes to the site.

The Durham team spent some time at the bus stop on West Club Boulevard observing how people cross the street and talking to bus riders about their experiences before and after making changes to the site.

Between online engagement and in-person intercept surveys, the Durham team connected with two very different groups within the community. The 126 respondents to the online survey were predominantly white and most frequently drove through the site. Most of them never walked or rode the bus at all. In contrast, the 46 people who participated in the first round of intercept surveys were walking by or waiting at the bus stop, and they were overwhelmingly people of color. The most common issue in-person interviewees raised was the lack of a safe, convenient place to cross, but people also expressed concerns that a crosswalk alone might not be enough to encourage drivers to yield on a street with so much speeding. They wanted to see more intensive safety treatments. Online, people also called for improvements such as crossings, road diets, and bike lanes. This dual insight played a huge role in shaping Durham’s demonstration project to better serve the needs of people who walk and ride the bus on a day-to-day basis while still balancing the needs and concerns of people who drive.

“Online engagement is such low-hanging fruit and doesn’t take much effort at all whereas intercept surveys are more effort and time but are so important to capture the range of voices we want to hear from in our community.”

—Anne Phillips, City of Durham

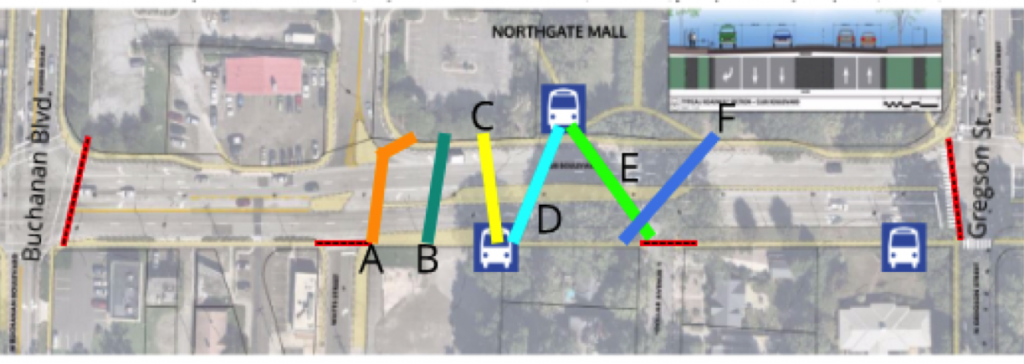

The most common crossing patterns observed at the site were D and C, where no crosswalk was present. Based on these observations, and based on feedback from the community, the Durham team developed a concept to install a new mid-block crosswalk with a protected pedestrian refuge.

The most common crossing patterns observed at the site were D and C, where no crosswalk was present. Based on these observations, and based on feedback from the community, the Durham team developed a concept to install a new mid-block crosswalk with a protected pedestrian refuge.

Just before the Durham team installed their project on the ground, a driver struck and injured a person biking on West Club Boulevard just outside the limits of the soon-to-be demonstration. This crash, coupled with the team’s proactive communication about the upcoming installation, caught the attention of local bike advocates, who reached out to the team to push for more permanent solutions and to volunteer their assistance. This started an important dialogue between the team and the advocates about the need for data-driven solutions. The bike advocates volunteered their time to help continue community engagement after the project launched to evaluate how people felt about the improvements. Working together, the project team and bike advocates conducted another 46 intercept surveys, and the team also continued collecting input from another 231 people through another online survey.

Creating a slower, safer street

Based on the input the team received online and through in-person engagement, they decided to install a mid-block crossing with a protected pedestrian refuge on the concrete median. They also implemented a road diet by closing the outside lanes of traffic, providing additional space for buses to pull over and encouraging drivers to slow down when approaching the crosswalk. To further strengthen the project, the team partnered with a local artist to design artwork for the median and the sidewalks. They brought several of the artist’s concepts to festivals and pop-up meetings to get people excited about the project and start important conversations about safer street design. In total, 348 people voted on the crosswalk art design.

The Durham team spreads the word about their project and asks for input on future art for the new crosswalk.

The Durham team spreads the word about their project and asks for input on future art for the new crosswalk.

The Durham team constructed a protected pedestrian refuge within the existing median. They also closed a lane of traffic and created a separate space for buses to pull over at the bus stop.

The Durham team constructed a protected pedestrian refuge within the existing median. They also closed a lane of traffic and created a separate space for buses to pull over at the bus stop.

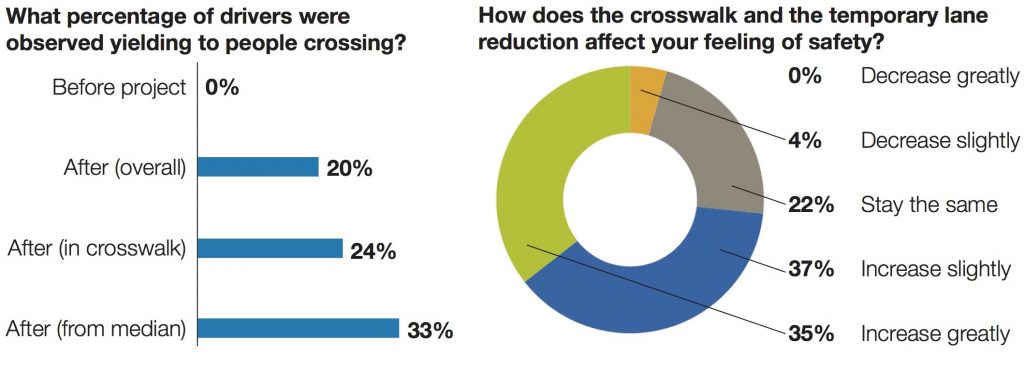

The results of Durham’s project speak for themselves. The team collected data before and after the project to measure changes in how people move through the space. Prior to their demonstration, zero percent of drivers yielded to people crossing the street between the bus stop and the shopping mall, but after they installed improvements this rose to 20 percent. Additionally, median driving speeds dropped from 30-33 miles per hour to 28-29 miles per hour. That may not sound like a lot, but a difference of five miles per hour can make a huge difference for safety, greatly reducing the likelihood of a crash and the severity of injuries should a crash occur. Furthermore, 73 percent of people who participated in intercept surveys following the installation reported feeling an increased sense of safety thanks to the changes.

Moving forward, the team will continue to introduce more permanent improvements to make the new crosswalk even safer. They are excited to install the artwork people voted on later this summer, and they also plan to add pedestrian-activated flashers at the crosswalk to further encourage drivers to properly yield.

Crews are currently implementing a temporary lane reduction on W. Club Blvd. The lane reduction will slow speeds on this segment of W. Club, making the area safer for all roadway users. pic.twitter.com/UuWd4tKbaV

— Durham Transportation Department (@movesafedurham) May 31, 2019

Awesome! Much needed connection to make northgate walkable

— Erik Myxter-Iino (@emyxter) May 31, 2019

Many thanks to our fantastic @movesafedurham staff for implementing this demonstration project on W. Club. I’m optimistic that the results will show that implementing these changes throughout this corridor will make for a safer Durham for all of us. https://t.co/MQ4R2cP5QP

— Charlie Reece (@CM_CharlieReece) May 31, 2019

Durham’s project received a lot of positive attention on social media, including from a city councilmember (right).

Lessons learned

Based on Durham’s experience transforming West Club Boulevard, communities around the country can learn from the following lessons to launch their own safety demonstration projects:

1. Different outreach methods reach (and miss) different parts of the community.

By conducting in-person intercept surveys, the Durham team connected with people they do not usually reach through online engagement. This ensured their project reflected the needs and desires of the most vulnerable people who use the street on a day-to-day basis, not just people who pass through. Even though this in-person engagement required more time and effort, it was indispensable to making sure the voices guiding this project reflected the community who stood to benefit most from safety improvements, especially people from low-income communities, communities of color, and people who do not own a car.

2. Collaborate with unexpected allies and partners.

The Durham team worked closely with contacts at local media sources to spread the word about their project. This outreach got people excited about the demonstration project and helped ramp up their community engagement both online and at events. In addition, they collaborated with a local artist, who previously submitted a portfolio to the city, to add a memorable creative placemaking element to their project, which they will install later this summer. Finally, their proactive social media communication following a nearby bike crash got the attention of local bike advocates who volunteered to help with interviews to evaluate the project and who have expressed interest in advocating for permanent improvements. These are all great examples of how the Durham team made the most of existing partnerships and potential allies to strengthen support of their demonstration project.

3. Do not miss the chance to keep the momentum going.

Thanks to all the attention and support for Durham’s demonstration project in the media and on social media, the team has momentum to carry out more intensive, permanent changes. Moving forward, they are exploring opportunities to install more intensive signals at the new crosswalk to further improve safety for people walking. Communities looking to implement similar projects should also be prepared to seize this momentum from an exciting, successful demonstration, either to work toward permanent improvements at the same site or to launch additional projects at other dangerous places.

The Durham team celebrated the success of their demonstration project during the final Safe Streets, Smart Cities Academy workshop in Pittsburgh.

The Durham team celebrated the success of their demonstration project during the final Safe Streets, Smart Cities Academy workshop in Pittsburgh.

—

The Safe Streets, Smart Cities Academy is funded by Road to Zero, a coalition of over 900 organizations committed to reducing traffic fatalities in the United States to zero over the next three decades.

Related News

© 2025 Smart Growth America. All rights reserved

Site By3Lane Marketing