News

By Sean Doyle, November 19, 2018

An art project about the historic streetcar in the border communities of El Paso, TX and Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, sparked public interest and then took on a life of its own. This month, the streetcars that once rolled through both border communities are back on the streets of El Paso, a demonstration of the power of art to capture the imagination of a community and create a better future.

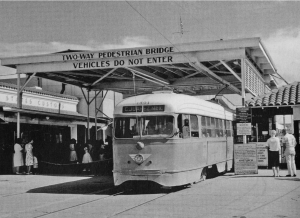

El Paso, TX and Ciudad Juárez, Mexico sit immediately adjacent to one another, separated only by the Rio Grande River and the international border between the U.S. and Mexico. Today, the two cities form the world’s largest binational metroplex, with billions of dollars in trade and thousands of daily crossings by foot, car, and bus. And until 1974, many of those border crossings were  facilitated by a streetcar system that connected the two cities (pictured left).

facilitated by a streetcar system that connected the two cities (pictured left).

The iconic, art deco streetcars and stories of their transnational past served as the inspiration for Peter Svarzbein’s masters thesis project at New York’s School for Visual Arts in 2010.

Svarzbein, a native of El Paso, created the El Paso Transnational Trolley Project, which could be described as part performance art, part guerrilla marketing, part visual art installation, and part fake advertising campaign. During our Intersections conference earlier this year, Svarzbein described his thesis as “a love letter to the city that raised me and my region.”

The project began with a series of large posters in downtown El Paso and Juárez advertising the return of the El Paso-Juárez streetcar, and continued with the deployment of Alex the Trolley Conductor, a new mascot and spokesperson for the alleged new service (pictured right). Alex appeared at Comic Cons, public parks, conferences, and other events to promote the return of the streetcar. Alex and the posters caught the attention of local residents and media, sparking curiosity and excitement for what many assumed was a real project.

The project began with a series of large posters in downtown El Paso and Juárez advertising the return of the El Paso-Juárez streetcar, and continued with the deployment of Alex the Trolley Conductor, a new mascot and spokesperson for the alleged new service (pictured right). Alex appeared at Comic Cons, public parks, conferences, and other events to promote the return of the streetcar. Alex and the posters caught the attention of local residents and media, sparking curiosity and excitement for what many assumed was a real project.

According to Svarzbein, one of the guiding principles of the project was to help the city and region “imagine a better future, because if you can’t imagine a better future you can’t have one.”

"An artist thinks differently, imagines a better world, and tries to render it in surprising ways. And this becomes a way for his/her audiences to experience the possibilities of freedom that they can’t find in reality."

– Guillermo Goméz-Peña

Back to the future

Svarzbein returned to El Paso after his thesis wrapped up in 2011. Given the local attention that the Transnational Trolley Project had garnered and the city’s plans to sell the old streetcars—which had been stored on the edge of town, open to the elements since 1974—he began a campaign to bring back a vintage trolley line with the original El Paso streetcars.

After gathering thousands of signatures in support of the project, the City of El Paso approached the Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT) for a $97 grant to build a streetcar line in the city. TxDOT agreed, if the city pulled together shovel-ready plans for the line and rounded up $4.7 million in local funding. El Paso did so, and then waited. A new mayor came to power, and “political winds began to shift, so rather than wait,” Svarzbein ran for city council to make this streetcar a reality. In July, 2015, Svarzbein won a seat as the District 1 representative on the city council.

The streetcar line did eventually receive its funding and while new tracks were being laid in the streets, the old streetcars were pulled out of the desert and restored to their original glory with some modern touches, like air conditioning, wifi, and bike racks.

The streetcar line did eventually receive its funding and while new tracks were being laid in the streets, the old streetcars were pulled out of the desert and restored to their original glory with some modern touches, like air conditioning, wifi, and bike racks.

Last Monday, November 12, 2018, the El Paso Streetcar opened for full service, with two interconnected, uptown and downtown loops. The loops connect the University of Texas at El Paso with many other neighborhoods and downtown.

A transnational future

As a city councilman, Svarzbein voted for phase 2 of the streetcar—which would extend the service to the El Paso Medical Center of the Americas—and introduced legislation to do a feasibility study on phase 3, which would restore transnational service to Ciudad Juárez.

In the El Paso region, “we’ve always viewed the border as an opportunity, not as a threat,” according to Svarzbein. A transnational streetcar system would provide greater economic opportunity for the entire region, enhancing relations between the two sister cities and facilitating the exchange of goods and ideas. To that end, as part of the regional 2045 plan—Destino 2045—there is an international pedestrian transportation system envisioned within the next 10-15 years.

In the El Paso region, “we’ve always viewed the border as an opportunity, not as a threat,” according to Svarzbein. A transnational streetcar system would provide greater economic opportunity for the entire region, enhancing relations between the two sister cities and facilitating the exchange of goods and ideas. To that end, as part of the regional 2045 plan—Destino 2045—there is an international pedestrian transportation system envisioned within the next 10-15 years.

The story of El Paso's streetcar is another example of how transportation professionals are exploring new, creative, and contextually-specific approaches to planning and building transportation projects. They are collaborating with artists and the community in new ways to transform transportation systems into powerful tools to help people access opportunity, drive economic development, improve health and safety, and build the civic and social capital that binds communities together.

Related News

© 2026 Smart Growth America. All rights reserved

Site By3Lane Marketing