News

By Sean Doyle, September 25, 2019

The average American currently drives nearly twice as far each day as they did 30 years ago. Taking a cursory look at two radically different transportation plans for Houston, TX shows how the default position of federal transportation policy is to increase driving—and consequently pollution—by offering billions to states to build new roads and make existing roads wider, while making transit projects wait in line or compete for much smaller amounts of funding.

Right now, there are two major transportation plans being considered in Houston that would have dramatically different impacts and be funded in remarkably different ways. The first would fund a massive expansion of highways around the city’s downtown. The second is a plan to expand and improve transit offerings in the city. Both are purportedly about easing congestion and both cost around $7 billion. The highway expansion would be funded by the state DOT, primarily with federal funds they automatically receive every year, while the transit expansion would be funded through a combination of smaller federal grants they must apply and wait years for, local funding, and billions in bonds (assuming voters approve the sale of bonds this November).

Here’s a closer look at each of the transportation plans and the impact they would have on the city.

The transit plan

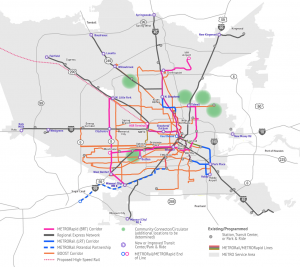

METRONext Moving Forward would build “over 500 miles of travel investments and enhancements.” The plan calls for 16 miles of new light rail lines, including a connection to Hobby airport and 75 miles of new bus rapid transit that will serve five heavily traveled corridors, including a connection to Bush Intercontinental airport. Twenty-one new and improved park and rides and 110 miles of “regional express service” will expand commuter service in the city. Existing bus routes that cover 290 miles will also get enhanced bus shelters and improved lighting.

METRONext Moving Forward would build “over 500 miles of travel investments and enhancements.” The plan calls for 16 miles of new light rail lines, including a connection to Hobby airport and 75 miles of new bus rapid transit that will serve five heavily traveled corridors, including a connection to Bush Intercontinental airport. Twenty-one new and improved park and rides and 110 miles of “regional express service” will expand commuter service in the city. Existing bus routes that cover 290 miles will also get enhanced bus shelters and improved lighting.

The plan was developed by METRO, Houston’s regional transit provider. It would give a welcome boost to transit service and build on recent efforts to improve the existing system in this sprawling metropolis. But it’s far from a done deal. Altogether, these transit improvements will cost an estimated $7.5 billion. $3.5 billion will come from bonds if voters approve their sale in a referendum this November. If the referendum fails, the plan will grind to a halt and it’ll be back to the drawing board. Assuming it passes (update: voters approved the referendum), the remaining $4 billion would come from a combination of federal grants that the city will apply for and existing METRO funding.

Like many regional transit plans, Metro Next has to balance two competing priorities. On the one hand, it seeks to improve service in the densest parts of the city that can most benefit from transit. On the other, it has to address the needs of every part of the metro that it serves in order to garner the broad public support necessary to win votes. It’s a common challenge facing many metro areas like Denver, Detroit, and Atlanta and it’s largely a function of how we fund transit in the U.S.—through new taxes or bond sales at the local level in combination with federal grants. The uncertainty and complexity around transit funding stands in sharp contrast to the way we fund highways.

The highway plan

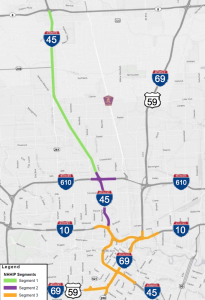

The North Houston Highway Improvement Project as the plan is known would affect all four interstates in the city: I-45, I-69, I-10, and I-610. While the plan is very complex, it would essentially add five travel lanes plus multiple full shoulders to I-45 north of downtown (segments 1 & 2) and route I-45 to the other side of downtown necessitating the reconstruction of all the downtown highways (I-45, I-10, I-65) and their interchanges.

The North Houston Highway Improvement Project as the plan is known would affect all four interstates in the city: I-45, I-69, I-10, and I-610. While the plan is very complex, it would essentially add five travel lanes plus multiple full shoulders to I-45 north of downtown (segments 1 & 2) and route I-45 to the other side of downtown necessitating the reconstruction of all the downtown highways (I-45, I-10, I-65) and their interchanges.

The stated goal of this $7+ billion project is to reduce congestion, though as Jeff Speck noted in a recent piece in the Houston Chronicle, “The costs are best understood as tremendous, and the benefits are best understood as false.” Wider highways don’t actually reduce congestion—if anything they make it worse. The Katy Freeway (a portion of I-10 just west of Houston) demonstrated that point locally when most commute times increased after a multibillion dollar widening that was completed in 2008.

But putting the futility of highway widenings aside, the Texas Department of Transportation’s (TxDOT) own documents describe the enormous impacts of this plan on surrounding communities: “displacement of residences and businesses, loss of community facilities, isolation of neighborhoods, changes in mobility and access, and increased noise and visual impacts…All alternatives would require new right-of-way which would displace homes, schools, places of worship, businesses, billboards, and other uses.”

Some 1,235 residences home to about 5,000 people will be torn down to make way for more pavement. Three hundred and thirty-one business employing 24,873 people will also be displaced, which “would have a negative impact on the local economy,” according to TxDOT.

A transit project with those negative impacts would never be approved. But the federal government doles out some $40 billion every year to state DOTs like TxDOT to do whatever they please with. (Many states choose to ignore their repair needs while building massive new highways. Texas spends 48 percent of its highway funds on expansion and 15 percent on repair.) Unlike the transit plan that will be the subject of great public scrutiny and a popular vote, there will be no public votes on funding this massive highway plan. And unlike the transit plan it will serve a much smaller portion of the city and actively displace thousands of people.

TxDOT has decided that instead of investing in a regional rail network, assisting communities with transit, or reducing the need to drive, the best thing the agency could possibly do with $7 billion is widen and reroute highways in Houston.

We should note that TxDOT lauds the possible addition of green space that could be created by putting some freeway segments below grade and capping them as this presentation shows. But funding for those parks is not included in the $7 billion price tag—other funding would have to be found. The cost of acquiring the land needed to widen the freeways, in some cases doubling their width, is also not included in the $7 billion figure.

These two plans in Houston illustrate how we actively undercut transit investments by also continuing to spend billions on road projects that will only increase driving, pollution, sprawl, traffic fatalities, and car-dependence. There is no overarching goal of our national transportation policy save for some version of “move cars fast always,” which is basically just a holdover from the 1950s when we set out to build the interstate highway system. That was completed 27 years ago and currently policy is now wildly out of step with modern day needs, not least of which is addressing climate change.

Instead of trying to build our way out of congestion (we can’t), we should instead focus on moving people. Are we using public funds and public land to connect more people to jobs and services. Will this transportation project give more people access to medical care, food options, or places of worship? Will this serve multiple modes of transportation or only serve people who can afford a car? If we had a transportation system that used the efficient movement of people as the metric for success, we’d evaluate the merits of these two plans far differently.

Related News

© 2025 Smart Growth America. All rights reserved

Site By3Lane Marketing