News

By Sean Doyle, November 6, 2019

U.S. transportation policy focuses first and foremost on ensuring that drivers can travel with as little delay as possible. But this laser focus on speed sidelines other more important considerations like the preservation of human life and the health impacts of vehicle pollution. Prioritizing safety in our transportation policy—at the federal, state, and local levels—would be a major step towards a more equitable transportation system.

This post was originally published by Transportation for America, a program of Smart Growth America.

America's transportation system is fundamentally inequitable. More resources go to wealthier and more politically connected communities; streets are designed to prioritize high-speed (expensive) vehicles over the safety of people, walking, biking, or taking transit; everyday destinations are out of reach for many people who don't own or can't afford a car. Those are just a few obvious examples.

Equity is a key consideration throughout our new principles for transportation, but it’s at the heart of the second one: Design for safety over speed.

In the U.S., our overarching priority in transportation for the past century has been to help cars to go as fast as possible, all the time, no matter the context. The term jaywalking was invented to shame people who dared to use public space that was increasingly becoming the realm of cars alone. We bulldozed entire neighborhoods—almost exclusively communities of color—in cities around the county to make way for new interstates that enabled white flight. And as interstates and other roads filled with traffic we spent vast sums of public money to bulldoze even more homes and businesses to widen the roads, only to watch them fill up with even more traffic.

But our focus on prioritizing speed above all else with the public right-of-way has not had the same negative impact on everyone.

The pollution that this futile pursuit of speed has generated disproportionately impacts lower-income people and people of color. "On average, communities of color in the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic breathe 66 percent more air pollution from vehicles than white residents," according to the Union of Concerned Scientists. This pollution shortens lifespans and can have lifelong impacts from developmental problems in children to increased rates of asthma, diabetes, and other chronic health impacts.

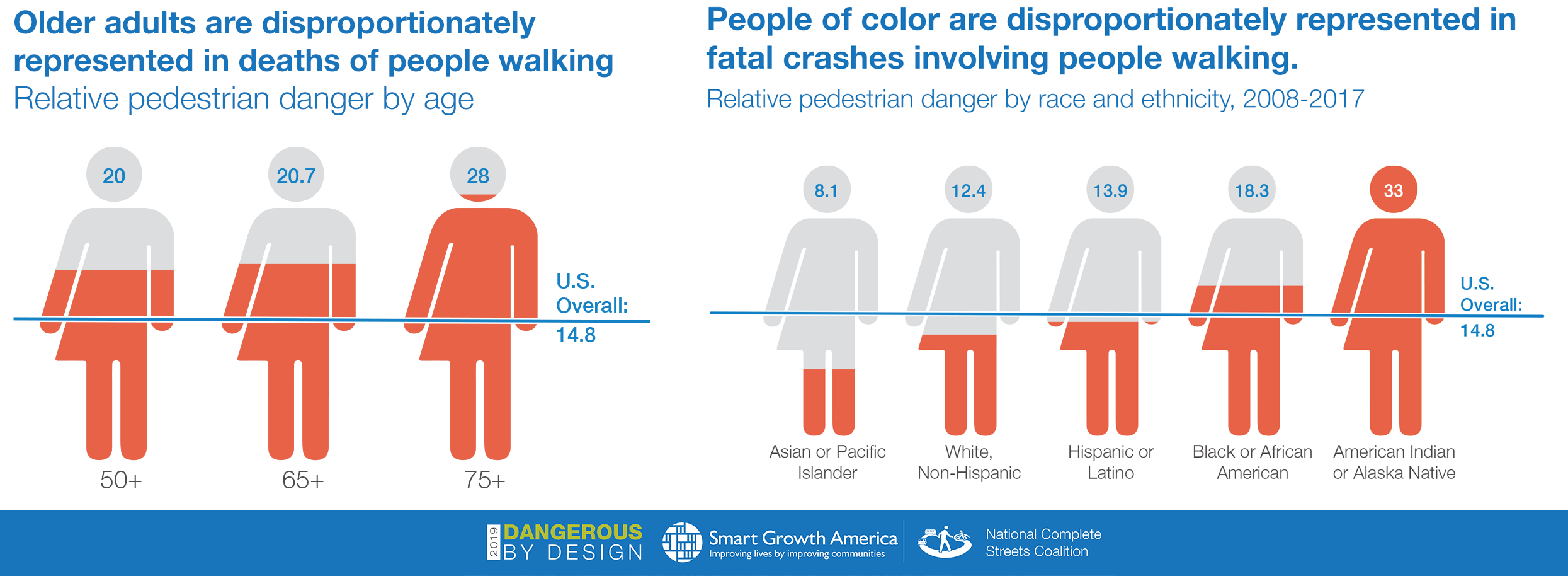

As our colleagues at Smart Growth America noted in Dangerous by Design 2019, "even after controlling for differences in population size and walking rates, we see that drivers strike and kill people over age 50, Black or African American people, American Indian or Alaska Native people, and people walking in communities with lower median household incomes at much higher rates."

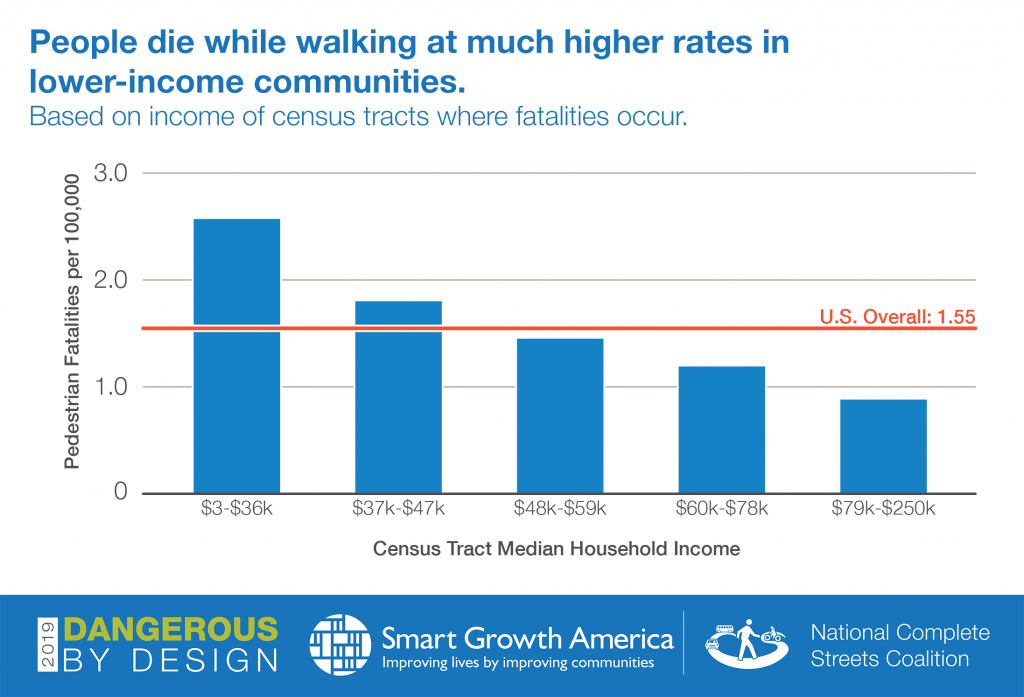

While federal data on traffic fatalities doesn't include information on a victim's income level, it does include where a person was walking when they were killed. And people walking in lower-income communities are far more likely to be struck and killed by drivers than people walking in middle-income communities. (One would logically assume that these victims are more likely to live in those lower-income communities.) The disparities in these fatality rates are a direct reflection of policy and funding decisions. Low-income communities are less likely to have sidewalks (in good condition), marked crosswalks, and street design to support safer, slower speeds.

We need to prioritize the safety of those outside of vehicles

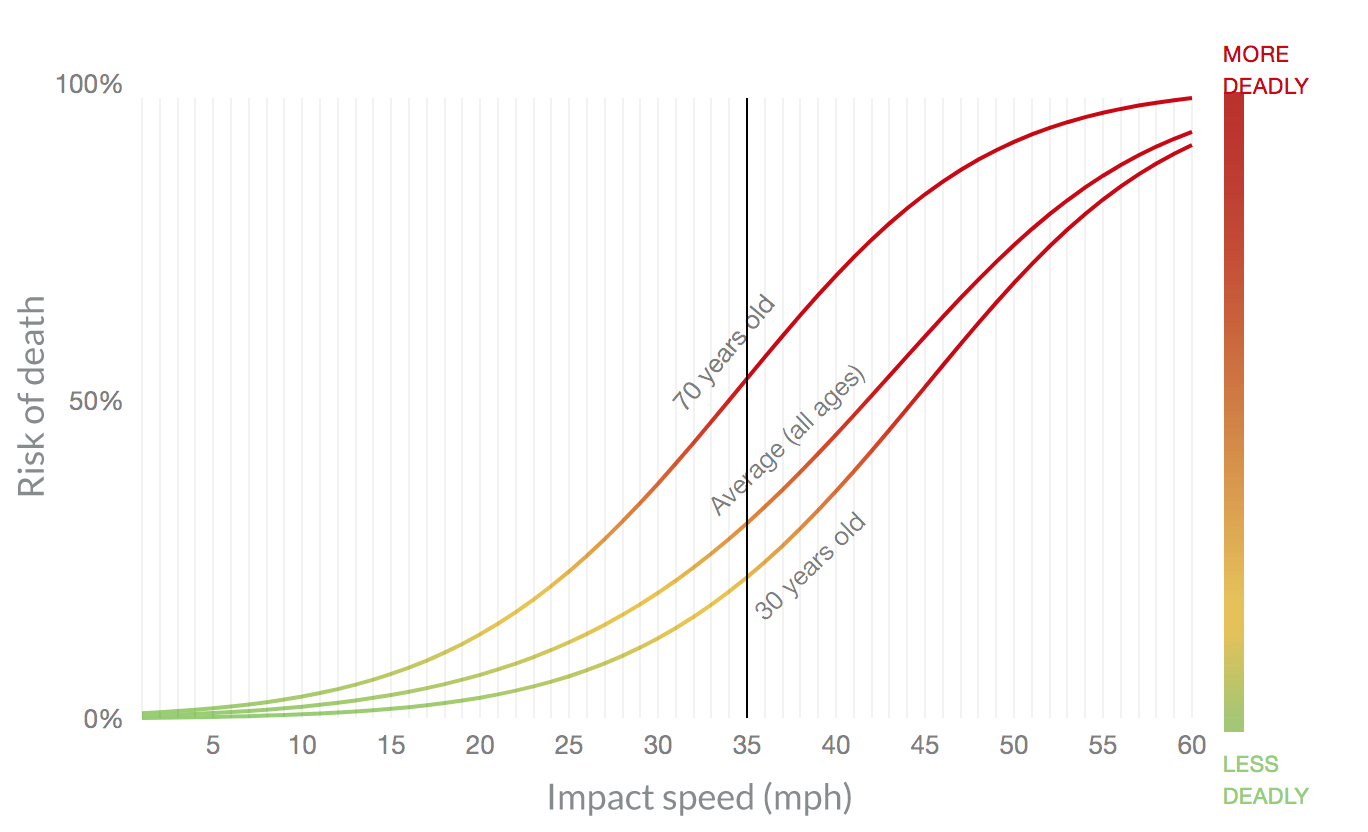

Part of the solution is making sure we're putting the safety of people walking, biking, and taking transit on equal footing with people driving. In most places, the people more likely to be traveling outside of a vehicle are people who have suffered the most from the previously outlined disparities and inequities. Our call to design local and arterial roads surrounded by development for no more than 35 mph would dramatically improve equity. When you have people walking, shopping, dining, waiting for the bus or otherwise going about their lives, roads designed for drivers to travel at 40 or 50 mph are simply too fast and too deadly. A pedestrian hit by a driver at 50mph is about twice as likely to die as a person hit at 35 mph.

See the full interactive graph at ProPublica.

See the full interactive graph at ProPublica.

To be clear, this isn't just a function of speed limits.

While lowering speed limits is important, what most people don’t understand is that once you’re behind the wheel of a car, you will drive at the speed you feel comfortable. Designing for safety is paramount. Wide, straight lanes and open skies give unspoken cues to drivers that this road is built for speed. In contrast, narrower, perhaps curvier lanes that are enclosed by buildings or streets trees signal to drivers that they should be driving slower.

Beyond being intentional about the safety of people outside vehicles, resource allocation is critical. Many federal grant programs for infrastructure projects, even small but critical ones like redesigning a deadly intersection, require a local funding match. But for many poor cities and towns—both rural and urban—securing such matching funds can be prohibitive. At the local level, officials need to be intentional about tracking where and how funds are being spent to ensure that the streets in lower-income areas designed for safe travel just more affluent areas.

Communities impacted by vehicle pollution should also have a larger voice in planning future transportation investments. Too often these communities are excluded, or their voices are given less weight than others even though they will be the ones who bear the greatest impact from a widening highway or larger road. One example of this is how most projects to widen or expand a roads typically only consider the limited improvements to travel time for commuters traveling through that area, while failing to consider the impacts on those who may need to cross that street, or the increased air pollution for those who live nearby.

It’s simply not part of the typical calculus; all of the underlying metrics in the federal transportation program focus simply on vehicle speed, delay, and throughput. Many states are even planning for more people to die in future years—it's an implicit acknowledgement that their streets are unsafe yet nothing in federal law requires them to try and kill fewer people. So many simply won't act.

Safety must be our priority. Making walking, biking, and taking transit safer will save lives and help reduce driving, in turn reducing the health disparities in low-income communities and communities of color.

In the end, this is about whether or not we value the lives of everyone. Today, our transportation policy—particularly at the federal level—values a few seconds saved for motorists each day over the lives of people walking, biking, or taking transit. It values the lives of the wealthy over the lives of low-income people. And it values the lives of white or more affluent Americans over the lives of other Americans. By putting safety at the heart of our transportation policy, we can start to create a more equitable transportation system.

Related News

© 2026 Smart Growth America. All rights reserved

Site By3Lane Marketing