News

By Smart Growth America, July 29, 2019

Pittsburgh’s demonstration project made it safer and easier to cross the streets surrounding an elementary school by reconfiguring a dangerous intersection and introducing protected pedestrian refuges at crosswalks.

Pittsburgh’s demonstration project made it safer and easier to cross the streets surrounding an elementary school by reconfiguring a dangerous intersection and introducing protected pedestrian refuges at crosswalks.

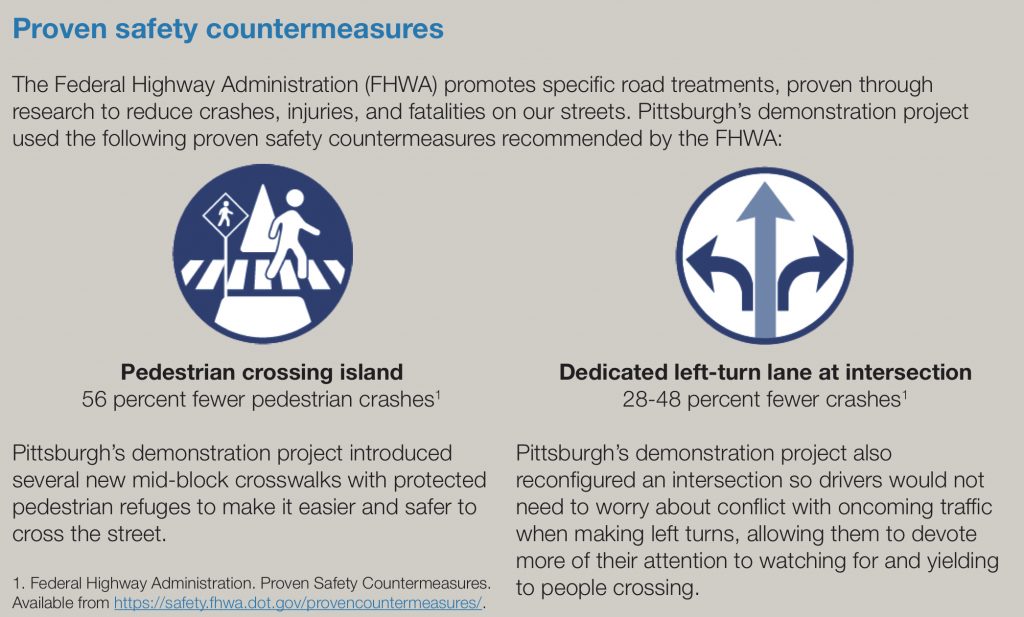

Through the Safe Streets, Smart Cities Academy, Smart Growth America worked with three cities around the country to implement temporary safety demonstration projects. The City of Pittsburgh historically relied on 311 requests to help decide which streets need safety improvements, but when a team from the city looked more closely at the data, they realized they were not reaching the whole community through this process. In particular, they were not addressing key locations with high crash rates in low-income communities of color because this traditional channel of collecting complaints. In partnership with the Southwestern Pennsylvania Commission, the Allegheny County Health Department, the Port Authority of Allegheny County, and PennDOT, they launched a demonstration project at one such site to implement safety projects and to establish new partnerships with the community. Working closely with a local school, they added crosswalks with protected refuges to help children reach school more safely, and they also redesigned the intersection of Lincoln and Frankstown Avenues to make it less stressful for all people—including drivers—in the process.

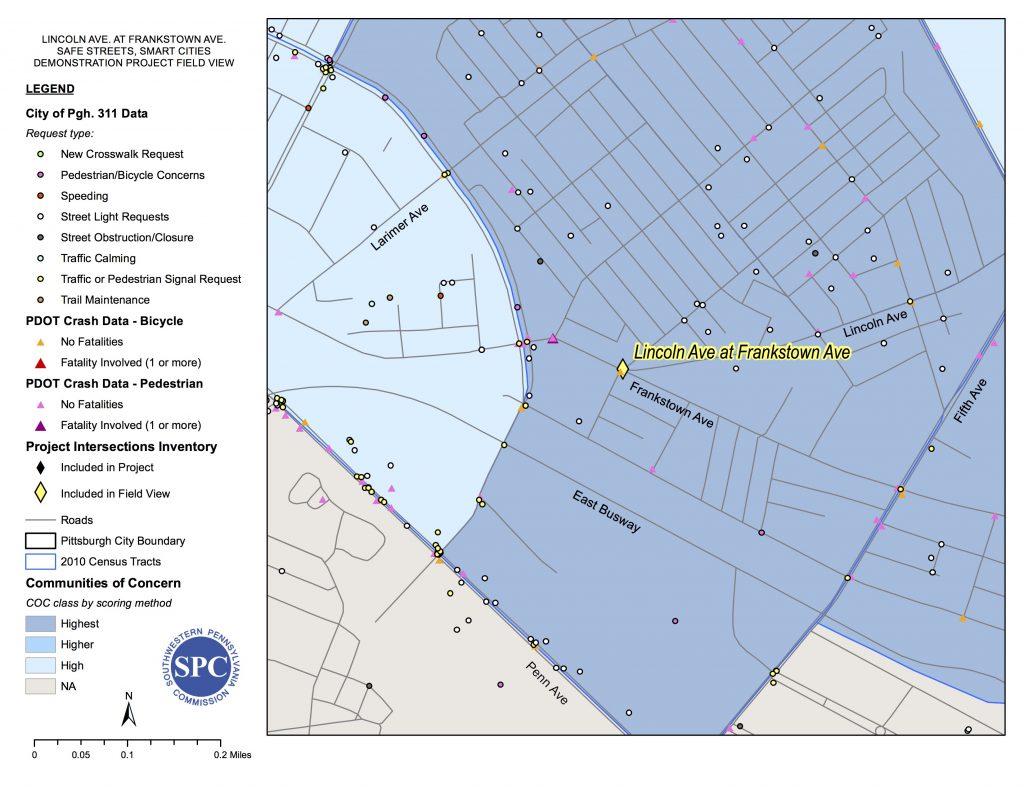

As part of the Safe Streets, Smart Cities Academy, staff from the City of Pittsburgh and partner agencies learned about inclusive strategies to engage the community, especially parts of the community who are most vulnerable to traffic crashes, including low-income communities of color. The team realized that a demonstration project would create the perfect opportunity to not only transform some of their streets into safer places for people, but also to pilot a new approach for engaging the community. They worked with the Southwestern Pennsylvania Commission, which serves as the metropolitan planning organization (MPO) for the Pittsburgh region. Using the MPO’s communities of concern analysis, which looks at income, English proficiency, educational attainment, race, and other factors, they identified sites in their most vulnerable communities with high crashes. Then, they explored which of these sites had few instances where people reached out to the city to complain to select possible places to stage their demonstration.

To choose the site of their demonstration project, the Pittsburgh team looked at the overlap between crashes, communities of concern, and gaps in 311 requests.

To choose the site of their demonstration project, the Pittsburgh team looked at the overlap between crashes, communities of concern, and gaps in 311 requests.

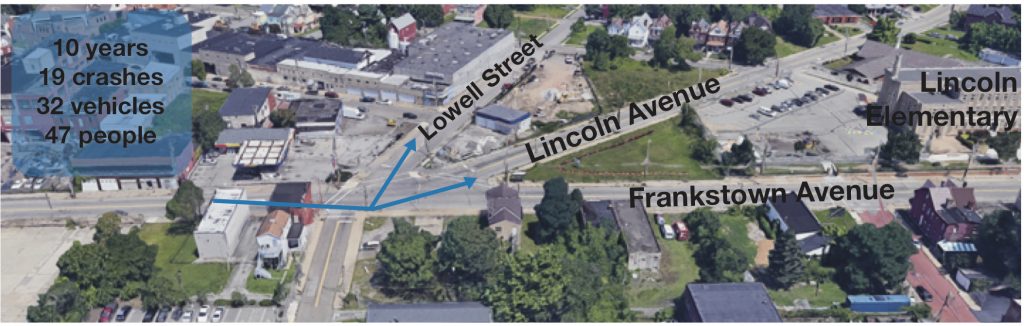

The team ultimately selected the intersection of Lincoln and Frankstown Avenues as the main focus for their project. This confusing, star-shaped intersection provides direct access to an elementary school. In just the past 10 years, 19 crashes occurred at this intersection, including several crashes involving people walking. When visiting the site, team members witnessed additional near misses between drivers and people crossing the street. People driving also regularly exceeded the school zone speed limit on both Lincoln and Frankstown Avenues, in some cases driving nearly twice as fast as the posted speed limit.

Most of the crashes at this intersection involved cars making quick left-hand turns from Frankstown Avenue onto either Lincoln Avenue or Lowell Street. This put children who cross this intersection to reach nearby Lincoln Elementary School at risk of being struck and injured or killed.

Most of the crashes at this intersection involved cars making quick left-hand turns from Frankstown Avenue onto either Lincoln Avenue or Lowell Street. This put children who cross this intersection to reach nearby Lincoln Elementary School at risk of being struck and injured or killed.

Despite the obvious dangers at this site, the city received very few complaints about it through Pittsburgh’s 311 hotline. They decided to use their demonstration project to start a much-needed dialogue about safer streets with residents of the neighborhoods surrounding the site, which tends to be lower-income, more racially diverse, and more transit-dependent compared to other parts of the city. This shift in focus will help the city work toward a commitment to eliminate all traffic deaths on their roadways through a Vision Zero initiative. This Vision Zero approach will also work to prioritize the most vulnerable people who use the road who have been consistently left behind in previous community engagement.

“Vision Zero is helping us to reframe that question

about where we really need to focus our energy.”

—Katy Sawyer, City of Pittsburgh

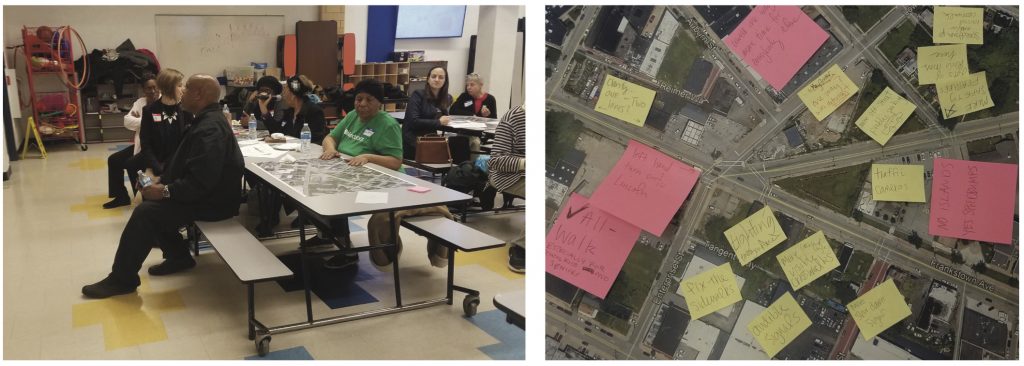

The Pittsburgh team led a deliberative democracy forum with break-out discussions, an expert panel, and a design exercise to engage the community and guide their demonstration project.

The Pittsburgh team led a deliberative democracy forum with break-out discussions, an expert panel, and a design exercise to engage the community and guide their demonstration project.

Engaging the community

To make sure the community had a meaningful voice in guiding their demonstration project, and to start a robust dialogue about safer street design more broadly, the Pittsburgh team decided to use an engagement method called “deliberative democracy.” Rather than a standard town-hall meeting where the city educates attendees then attendees share feedback, deliberative democracy is a forum that works toward building consensus among participants. In this sort of forum, people break out into small group discussions, ask questions of an expert panel, and give detailed, specific input that helps guide decision-making. Pittsburgh has previously used this method to involve the public in decision-making surrounding their budget, but until now they had not used it as an engagement tool for standalone transportation projects. They worked with the mayor’s office to run the forum and spread the word through community neighborhood groups and flyers sent home through schools.

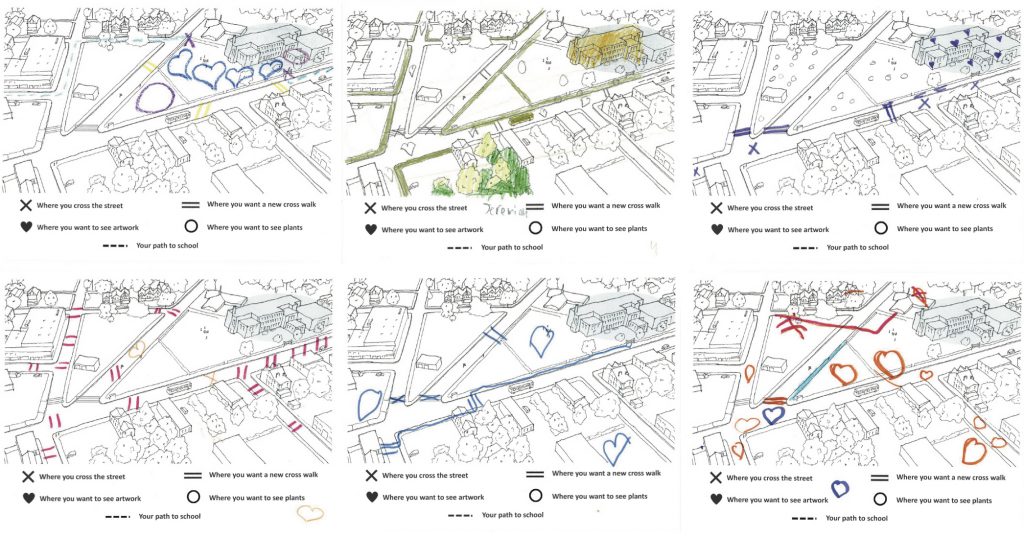

In addition, Pittsburgh partnered with the Allegheny County Health Department and PennDOT to engage directly with schoolchildren. The county regularly conducts classroom visits to teach seminars on safety, so the Pittsburgh team decided to use this as an opportunity to learn from kids about how they get to school, where they cross currently, and where they would like to cross if the street were designed differently. They brought maps to classrooms, meeting with approximately 250 children to ask them what they want the surrounding streets to look like. Based on the feedback the team received from schoolchildren and from their deliberative democracy meeting, they realized they needed to expand the bounds of their project to include the surrounding streets as well as the intersection.

Students from nearby Lincoln Elementary School drew on maps to tell the Pittsburgh team how they get to school currently and where they would like to see new and improved crosswalks.

Students from nearby Lincoln Elementary School drew on maps to tell the Pittsburgh team how they get to school currently and where they would like to see new and improved crosswalks.

To celebrate the launch of their demonstration project and show the community how their input led to safer street design, the team held a block party right after school dismissal. They brought food, music, chalk, and more information about the project to share with children, parents, teachers, and partner organizations. They also invited the local advocacy organization Vibrant Pittsburgh to parade across the new and improved crosswalks to raise awareness about safer street design.

At the launch event for their demonstration project, the Pittsburgh team educated drivers, parents, children, and partners about the new safety improvements.

At the launch event for their demonstration project, the Pittsburgh team educated drivers, parents, children, and partners about the new safety improvements.

Creating slower, safer crossings

The design of Pittsburgh’s demonstration project closely followed the feedback they received from the community. For example, by meeting with schoolchildren and asking them to draw on maps, they learned that kids have trouble crossing the street not just at the Lincoln and Frankstown intersections, but at many intersections and mid-block places surrounding the school. As a result, the team introduced several new and improved crosswalks nearby, many of which included protected refuge islands halfway across to provide a safe space for people to pause while crossing and to remind drivers to slow down and yield. They also included informational signs at several of the crosswalks to educate people about the new design and why it is important for safety.

In addition, they made more intense improvements at the Lincoln and Frankstown intersection thanks to insights gleaned from their deliberative democracy. During these conversations, the Pittsburgh team learned that one problem at the intersection leading to conflict between people driving and walking was how stressful and difficult it was for drivers to make left-hand turns. Drivers were so concerned about avoiding oncoming traffic, they were not paying close enough attention to people crossing the street. Using this input, the Pittsburgh team devised a solution that made the intersection safer and easier to navigate for everyone. They added a left-turn lane to the intersection and a corresponding left-turn phase to the traffic signal. This way, drivers would not need to worry about conflicts with oncoming traffic when making turns and could pay closer attention to people walking. This also allowed the team to add a pedestrian-only phase to the traffic signal, providing people with extra time to cross while cars are still stopped.

Using paint and temporary dividers, the Pittsburgh team created pedestrian refuge islands so people crossing the street would only need to worry about one direction of traffic at a time. This also narrowed the roadway approaching crossswalks, cuing drivers to slow down, pay attention, and yield to people crossing.

Using paint and temporary dividers, the Pittsburgh team created pedestrian refuge islands so people crossing the street would only need to worry about one direction of traffic at a time. This also narrowed the roadway approaching crossswalks, cuing drivers to slow down, pay attention, and yield to people crossing.

Educational signs reinforced Pittsburgh’s demonstration project and its importance for safety.

Educational signs reinforced Pittsburgh’s demonstration project and its importance for safety.

To start, the team made these improvements at very low cost using temporary materials like planters, spray chalk, cones, and plastic signs. Moving forward, they hope to make permanent safety improvements based on the response to their demonstration. In addition, they hope to apply the lessons learned from their successful community engagement to other transportation projects citywide, continuing to work with schoolchildren and to stage deliberative democracy meetings to give the community a stronger voice in decision-making.

Lessons learned

Based on Pittsburgh’s experience transforming Lincoln and Frankstown Avenues, communities around the country can learn from the following lessons to launch their own safety demonstration projects:

1. Community engagement should be proactive, not responsive.

The Pittsburgh team’s approach to identifying their project site—namely, looking for overlap between communities of concern, crashes, and a lack of 311 calls—is an approach other communities can emulate to identify gaps in their own engagement and safety efforts. Responding to complaints from the community can widen the gap between places that already experience transportation investment and places that experience systematic underinvestment. Thanks to this decision, Pittsburgh’s project helped them foster new partnerships and trust with a part of the community that they had not previously engaged, ultimately leading to a much stronger demonstration project.

2. Make the most of your existing partnerships.

The Pittsburgh team made great use of their existing partnerships and programs to strengthen community engagement for their demonstration project. They collaborated with the Allegheny County Health Department, who were already conducting classroom visits, to collect input from 250 children. They worked with the mayor’s office, whose staff had experience facilitating deliberative democracy forums for their budgeting process. Finally, they applied the Southwestern Pennsylvania Commission’s analysis on communities of concerns to help them identify a project site with huge potential to benefit the most vulnerable segments of the city’s population.

3. Look for win-win opportunities to make streets safer for everyone.

When it comes to safer street design, projects must often contend with trade-offs between high speeds for drivers and safer, slower speeds for people walking and biking. But Pittsburgh’s demonstration project shows that it is possible to redesign streets and intersections in a way that makes them safer and easier to navigate for everyone, including drivers and people walking. By reconfiguring the intersection at Lincoln and Frankstown Avenues to allow drivers their own phase for left turns and people walking their own phase to cross, they made the intersection safer, less stressful, and more comfortable for all people. These sorts of win-win design solutions are powerful opportunities to foster unified support for future projects, and they help dispel the notion that there always have to be trade-offs when creating safer streets.

The Pittsburgh team celebrated the successful launch of their demonstration project.

The Pittsburgh team celebrated the successful launch of their demonstration project.

—

Reminder: Join us on Thursday, August 1 at 2:00 p.m. to learn more about Pittsburgh’s street safety demonstration project and similar safety projects from Huntsville, AL and Durham, NC that were part of this year’s Safe Streets, Smart Cities Academy.

The Safe Streets, Smart Cities Academy is funded by Road to Zero, a coalition of over 900 organizations committed to reducing traffic fatalities in the United States to zero over the next three decades.

Related News

© 2025 Smart Growth America. All rights reserved

Site By3Lane Marketing