News

By Chris Rall, December 6, 2019

Chris Rall and his two eldest children on a family bike.

Chris Rall and his two eldest children on a family bike.

Our family is a biking family. For us, that means being healthy, active, and having a lot of freedom and mobility. Biking is how our family chooses to get around, but building a family-friendly city means having streets that can help people get around in any number of ways—walking, biking, transit, scooting, or driving.

My wife Becky, our twins, and I moved to Portland, OR in 2009 to live closer to extended family, but the city's reputation as a biking city was another draw. We are a family that mostly bikes to get around. Our twins were on balance bikes not long after learning to walk, and we strapped them into a bike trailer as soon as they could hold their own heads up.

Biking to get around kept Becky and me physically active, which gets harder to do when you are raising young kids. And while it’s not always the fastest way to get somewhere (sometimes it is) and it takes a bit more work to dress the kids properly for the weather, biking is reliable, we’re rarely stuck in traffic, and we like being outside. There's also no tailpipe spewing pollution into the air we all breathe.

In Portland, biking is one among many transportation options: there's transit and many communities are fairly walkable, but there's certainly room for improvements to make these options safe and accessible, much less preferable to driving. After all, a family-friendly city provides transportation choices to meet the needs of the moment: walking to school, taking transit out to dinner, riding a scooter to the corner store, or as is often the case for me, rolling out the bike.

I'll bike on almost any road, but I recognize that’s not for everyone. After all, you shouldn't need nerves of steel just to be able to bike around town. Living in a community with infrastructure to make biking as safe as possible becomes an imperative with a family in tow. Safe bike infrastructure for any age means car traffic is separated, or slow and light.

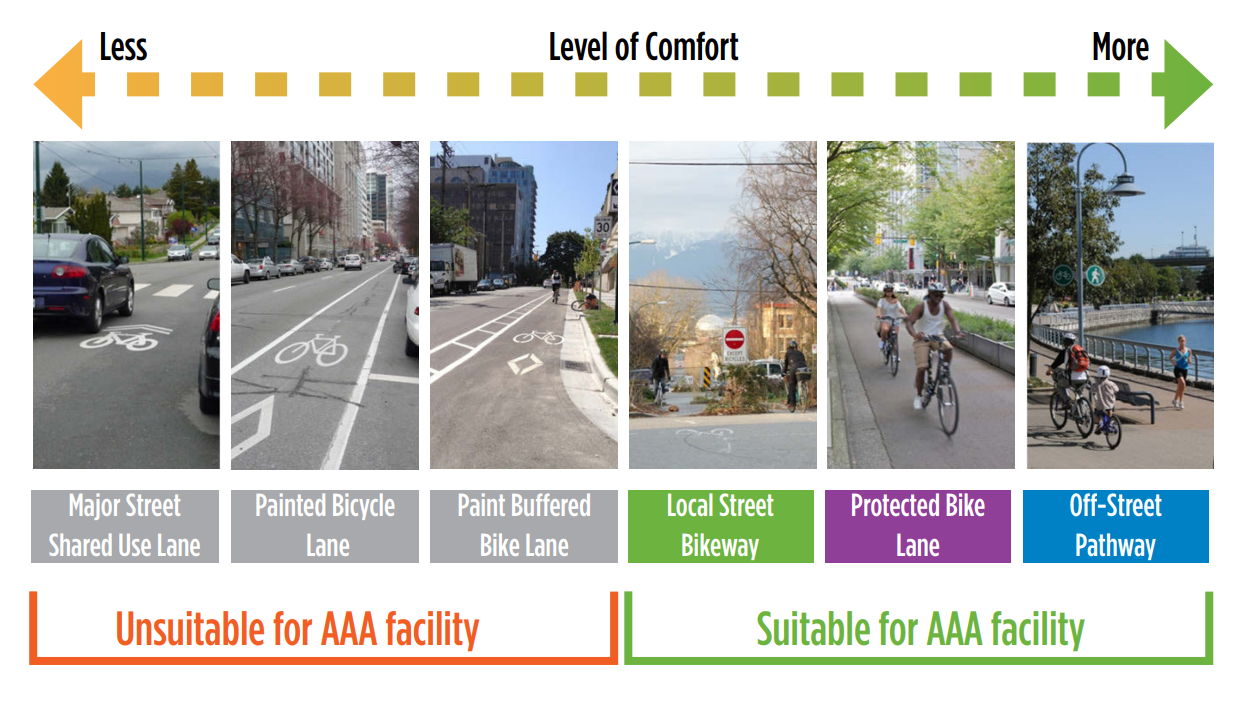

All ages and abilities (AAA) bicycle infrastructure. Graphic via the City of Vancouver Transportation Design Guidelines . A diverter can be seen on the "local street bikeway."

All ages and abilities (AAA) bicycle infrastructure. Graphic via the City of Vancouver Transportation Design Guidelines . A diverter can be seen on the "local street bikeway."

Portland’s bike network is mostly built around neighborhood greenways, also known as bike boulevards. These are neighborhood streets that have diverters and speed bumps to discourage and slow down car traffic, while allowing people on bikes to get where they need to go throughout most of the city.

The Portland Bureau of Transportation (PBOT) developed a policy several years ago to make sure neighborhood greenways stay bike-friendly. As a result, they add additional diverters and traffic calming to existing neighborhood greenways when they determine that cut-through traffic volumes have increased too much. Diverters are a relatively inexpensive way to prevent cars from passing through an intersection but allow bikes, creating a safe, low-stress environment for biking. Each new diverter is a like a breath of fresh air—you can breathe a little easier because you feel safer.

As our twins grew and we had a third child, we’ve used a lot of different contraptions to carry kids and associated stuff around—bike trailers, longtail bikes with more room for kids to ride on the back, and bakfiets where the kids (or cargo) ride in a big box on the front.

But one more recent innovation is a game-changer for biking, especially with a family: the electric bike. The extra boost electric bikes provide make it possible to carry heavier loads (like more/older children) and ride much further with relatively little effort and without arriving drenched in sweat. The pedal-activated electric motor we added to our longtail bike makes the bike an option for longer trips with the kids that I wouldn't have considered before. I also use the electric bike to attend exercise classes I know I’ll be too tired to ride home from.

The rise of electric bikes has big implications for public policy. For one, it makes biking accessible to more people in more situations—older Americans, people in hilly places, or people in hot weather trying to avoid sweating. Making biking more accessible is great, but more safe infrastructure needs to be available for people to actually opt for the bike—especially for families. Second, rebates for electric bikes should be considered alongside rebates for electric cars when governments are looking for ways to reduce emissions. The government rebates currently available for a single electric car could buy multiple electric bikes outright; a relatively small e-bike rebate could deliver a lot of bang for the buck in reducing emissions.

Investing in the kind of infrastructure to make biking safe and convenient and land-use policies that allow housing, jobs, and services to be built within bikeable distances are important elements of a community supportive of family biking. However, a family-friendly city prioritizes a range of options rather than forcing everyone to drive. My older son bikes to middle school, but his twin sister chooses to walk. My wife has been taking the bus more often lately to meet up with friends. I’ve used by-the-minute car rentals to meet my carpool ride up to the mountain for skiing. Having lots of transportation options gives us the freedom to get around in the way that works best for us. And that makes for a happy family!

Chris Rall is the Outreach Director for Transportation for America, a program of Smart Growth America, and is based in Portland, OR.

Related News

© 2025 Smart Growth America. All rights reserved

Site By3Lane Marketing