News

By Natasha Riveron, May 29, 2019

The Best Complete Streets Policies of 2018. They shared their insights on the process of passing a strong Complete Streets policy and answered viewers’ questions. A recording of the webinar is now available. You can also read the brief recap below.

The Best Complete Streets Policies of 2018. They shared their insights on the process of passing a strong Complete Streets policy and answered viewers’ questions. A recording of the webinar is now available. You can also read the brief recap below.

A discussion recap

Emiko Atherton kicked off the event by highlighting Complete Streets progress across the nation, noting that there are now nearly 1,500 Complete Streets policies in place across the country. She congratulated this year’s top ten communities on passing high scoring policies, especially this year given we used a new and improved grading framework—The 10 Elements of a Complete Streets Policy—for the first time.

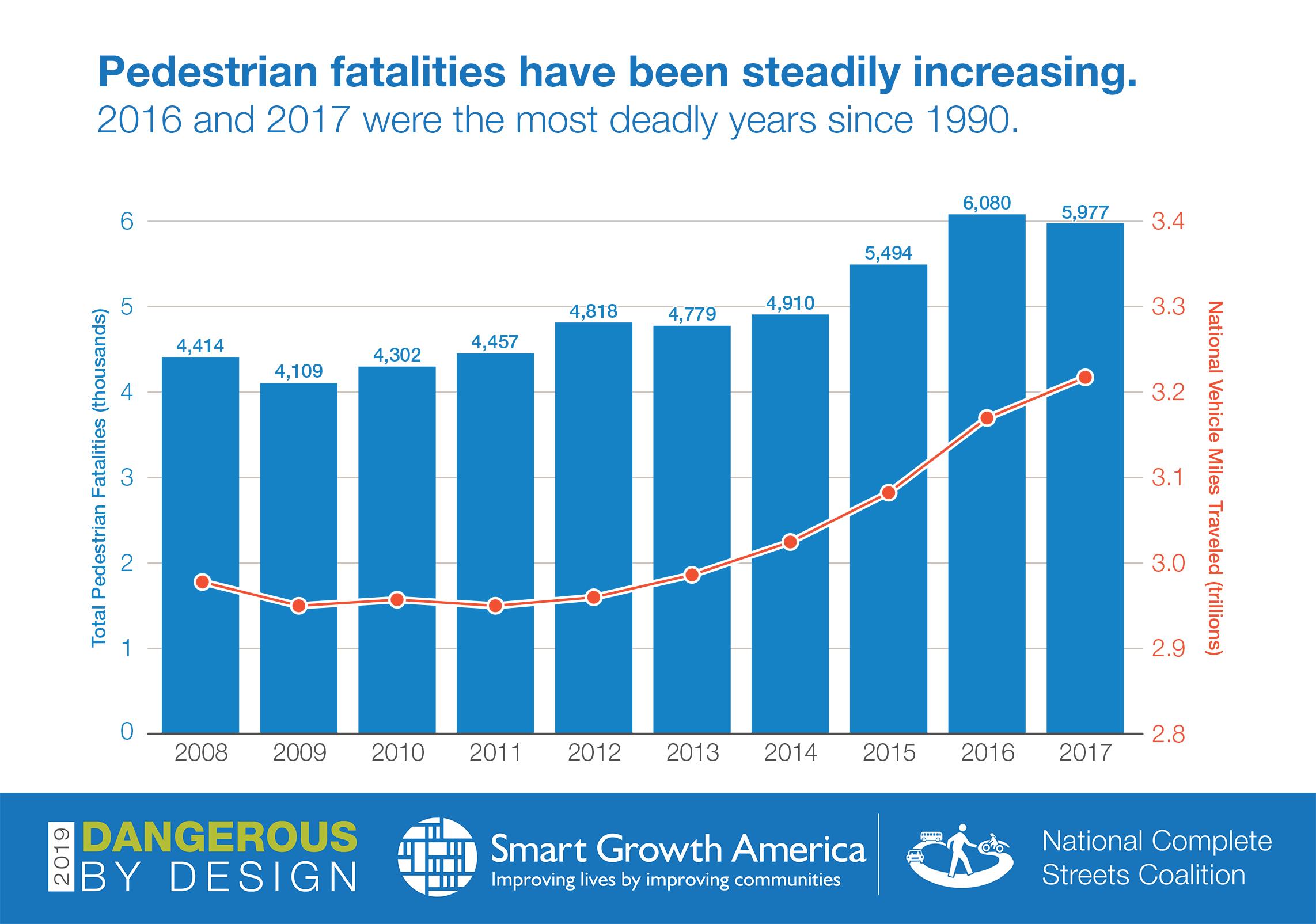

While the Complete Streets movement has gained momentum over the last decade, we are still killing pedestrians (particularly from vulnerable populations) at record numbers. Those deaths are caused by a culture that prioritizes the movement of cars over people’s lives. We know that Complete Streets policies alone won’t create safer streets; communities have to commit to change how they choose, plan, and build their street networks moving forward. That is why our new framework emphasizes implementation and equity in the Complete Streets policy itself.

While the Complete Streets movement has gained momentum over the last decade, we are still killing pedestrians (particularly from vulnerable populations) at record numbers. Those deaths are caused by a culture that prioritizes the movement of cars over people’s lives. We know that Complete Streets policies alone won’t create safer streets; communities have to commit to change how they choose, plan, and build their street networks moving forward. That is why our new framework emphasizes implementation and equity in the Complete Streets policy itself.

She then handed it off to Fred Jones, who talked about Neptune Beach, FL’s new policy. Fred is the vice mayor of Neptune Beach, a trained planner, Complete Streets advocate, and National Complete Streets Coalition Steering Committee member. Neptune Beach is a small coastal community in northeast Florida directly east of Jacksonville.

Neptune Beach began its Complete Streets journey because of the ranking that the Jacksonville metropolitan area (which includes Neptune Beach) earned in Dangerous by Design 2016; the metro area was the fourth most dangerous among of the country’s top 100 metros. Jones went on to emphasize the importance of messaging in Complete Streets advocacy, share elements of the city’s policy, and outline next steps for implementation and accountability in a small town with limited resources.

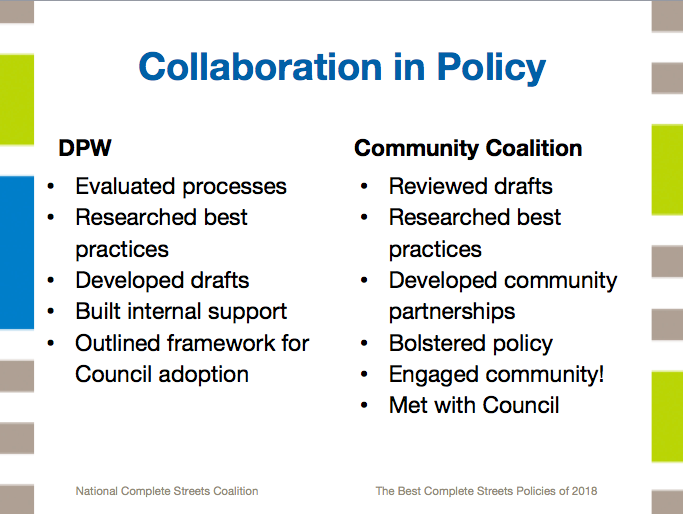

Next, we had two representatives from the Milwaukee Department of Public Works: Caressa Givens, community projects manager and James Hannig, pedestrian & bicycle coordinator. They shared how the city and a local coalition collaborated on drafting the policy and are continuing to collaborate on implementation. They also discussed how their process to discuss equity for their Complete Streets policy will be a framework for navigating hard conversations about addressing equity in transportation design and construction.

Next, we had two representatives from the Milwaukee Department of Public Works: Caressa Givens, community projects manager and James Hannig, pedestrian & bicycle coordinator. They shared how the city and a local coalition collaborated on drafting the policy and are continuing to collaborate on implementation. They also discussed how their process to discuss equity for their Complete Streets policy will be a framework for navigating hard conversations about addressing equity in transportation design and construction.

Finally we welcomed Richard Wong, planning director for Cleveland Heights, OH, the top scoring policy of 2018. His presentation was the most rhythmic and took a tour through the Ten Elements of a Complete Streets Policy, peppered with specific examples from Cleveland Heights.

Want to know more about these communities? Read their case studies in the Best Complete Streets of 2018 report.

Questions?

We had so many great questions during the Q&A section of the webinar that we couldn’t get to all of them. We followed up with all four of the speakers to discuss answers to some of the questions we missed.

James: This tension is real, but it might not be inherent.

Excellent community engagement should welcome all voices to the table, regardless of the level of support for a particular project (or element of a project). If any of the responses or voices is disproportionate, then more engagement is likely needed to make sure everyone, especially those affected, are heard. This doesn’t mean practitioners should engage until we hear what we want to hear, but it’s important to actually listen to all voices and take them seriously.

In Milwaukee, we have a project underway where we have overwhelming support from advocates supporting a two-way protected bike lane. However, several business owners along the corridor are not yet convinced. The city and our advocate partners have been meeting with supporters and opponents to listen to concerns and discuss ways of working through issues. Ultimately, we will not be able to satisfy everyone, but providing an atmosphere where people’s concerns are taken seriously can go a long way. For this particular project, we’ve even had a couple of opponents change their opinion after considering the project’s benefits in a different light.

Lastly, as the proverb goes, “Don’t let perfect be the enemy of the good.” Both in the example project and in developing our Complete Streets policy, there are times it felt like a side had to “win”. In these situations, I think it’s important to facilitate an environment where parties recognize that concessions will be necessary to produce something. It may not be perfect, but it is a start and it can be changed later. I remember a point in drafting the Complete Streets policy where it looked like everything was going to fall apart, and we were going to lose support from our partners. However, both sides were able to agree to a compromise because, at the end of the day, having a slightly less perfect policy was better than no policy at all.

Caressa: If you’re reading this you’re likely already convinced that there isn’t a single community that could not benefit from Complete Streets. How the need is communicated makes the difference for some of those tough groups opposed to change. Take time to listen to them, do your detective work, and discover how they’re connected to the decision-making process, and what they value.

For instance, a lot of people believe the solution to street safety is calling upon the police to solve the majority of their problems., One way that communities can accept how design can make significant positive changes is working with your local community liaison officer (CLO) to help deliver that message to some of those tougher groups. That is—changes to the streetscape that aim to make streets safer help the police do their jobs simply because they cannot be everywhere all at once. That message coming from the police could make more sense.

Fred: As elected official, I couldn’t get half of the things done without gaining at least informed consent. Many of the most vocal opponents are simply reluctant or fearful of change, but if you are transparent and continuously clarify your objectives, they will eventually get on board, even if they don’t agree. It’s also helpful to think about the spectrum of supporters and advocates and where they each fall relative to specific projects and initiatives. The International Association for Public Participation offers a great framework to build your engagement strategy by focusing first and foremost on what you want your desired outcomes to be and then appropriately matching the public engagement strategies to stakeholders. Far too often we merely “inform” and “consult” with the stakeholders that we need to be “empowering” and vice versa to build the capacity to successfully execute projects.

Fred: It plays probably the most important role. The consistent messaging for us around safety and local economy was central to unified support of the the Complete Streets policy. The Complete Streets imperative was built around getting Jacksonville off the Dangerous By Design top 10 list. That became the calling card that grabbed the attention of city leaders and the Chamber of Commerce.

Caressa: Branding and Marketing are huge. The Voices for Healthy Kids grant program that supports Complete Streets does an excellent job providing “text to action” resources, basic grassroots lobbying, and other professional marketing materials. It helps to have someone in-house too that can create an identity or a brand for you. Consider all the channels that your mission/vision and call to action will live on and design around the function.

Get a young person to work with you, young people are invaluable.

Close collaboration between the city and community partners was crucial in developing a unified message especially once the policy was finalized and ready to be promoted by everyone. Having this consistent, transparent message also went a long way in demonstrating the support and partnerships to elected officials which likely helped make the policy a “slam dunk” for Council adoption.

Richard: Back-in angled parking is safer for all users. It allows a driver full view of through traffic (including cyclists) when leaving the space. A lot of high schoolers bike to school thanks to the provision of ample well-designed bike parking and the bike repair station. In this age of tinted rear windows and tall vehicles, head-in parking is risky because of limited visibility backing into a through lane. Two other advantages are access to one’s trunk away from moving vehicles and when exiting with children, the open vehicle doors act as safeguards preventing vehicle occupants from straying toward moving traffic.

James: In Milwaukee, we’re just getting started, but we have funding to develop a Complete Streets handbook which will likely organize a number of policies, processes and design guidance that designers, planners, and engineers will have as a resource for implementing Complete Streets. Our policy also specifically references a number of design resources, most notably NACTO guides, as the backbone of design guidance. One of the first agenda items for our Complete Streets Committee is to endorse NACTO.

Richard Wong: Cleveland Heights was general and flexible with the intention of finding the most suitable state of the art design practices. The on-street, accessible van parallel parking, for example, was found in a research paper about future best practices and future ADA on-street requirements.

Using Google street view, I typically sketch ideas for reconfiguration with simple Microsoft PowerPoint “insert” and “shapes” functions. Each road has its unique constraints that require customized, quirky design solutions that are often not addressed in design manuals.

James: Unfortunately, public art was overlooked a bit when developing Milwaukee’s policy. However, as we have more conversations about implementing context-sensitive Complete Streets, we’re mindful to start discussions with rethinking how streets look and feel. While public art isn’t explicitly included in the policy, the ultimate goal is to reimagine streets as places that are safe and enjoyable. Milwaukee recently launched a Decorative Crosswalk program and we’re exploring many other opportunities to be more creative with street space.

Fred: Yes, this should be a central strategy of all Complete Street initiatives. The Florida Department of Transportation has a Community Feature Aesthetic Agreement MOU process to provide for roles and maintenance responsibilities associated with the installation of public art and design features on state owned infrastructure. For Neptune Beach, we are currently working to have murals painted on an overpass facility as a low cost way to provide a gateway treatment in concert with sidewalk and crosswalk enhancements underneath the bridge structure.

James: In Milwaukee, we’re having similar conversations on a few projects. As is likely similar in many communities, parking is a contentious topic and many business owners expect parking directly at their storefront. One approach that has been working for us is to describe, and show images of, the existing and proposed streetscape in terms of someone walking by their business. For example, on a current project, we’re proposing replacing angled parking with parking protected bike lanes. While this will result in a net loss of parking spaces, we’ve described the following benefits to the businesses and their customers:

- There should be more foot traffic as people will feel safer and more comfortable walking on the sidewalk.

- Pedestrians will also feel more comfortable having more distance between them and parked cars (which is particularly nice in sidewalk dining areas).

- People driving and biking will also be traveling at slower speeds which will mean they will be more likely to see storefronts and signs (and more likely to stop).

Richard: Support for bicycling can receive much-needed boost by having regular cyclist patrons speak to hesitant business owners. And study the use of those parking spaces. In Cleveland Heights, those one or two spaces in front often served as parking for a restaurant manager and one late-arriving employee instead of serving patrons who supported the business. Your findings may indicate that bike lanes could help more people than parking.

Richard: Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design (CPTED) teaches that eyes on the street—through requirements like storefront see-through windows and front doors, as well as pedestrian amenities and outdoor seating and tables on the sidewalk—add to the comfort of pedestrians. Good lighting, though expensive, makes a difference and is especially important at crosswalks. Colorful plants and public art also should be added. If the city pays for the improvements, require in an agreement that the businesses take care of the furnishings and landscaping so buy-in exists. I’ve found without buy-in, my city’s investments were not well-maintained.

James: Crime and violence—including traffic violence—is a barrier to biking and walking in Milwaukee. I think it’s important for communities to acknowledge that traffic violence is also real and deserves equal attention given to other crime. It is also important to engage with and foster a good relationship with police departments. It’s critical for the police to be an active part of developing and implementing a Complete Streets policy. While enforcement is only part of the equation to make streets safer for walking and biking, it’s critical to bring community members, police, and others involved with implementing Complete Streets together to set the expectations for realizing safe and comfortable streets. No one partner can do it alone, but the impact will be greater if concerns can be addressed together.

As far as safety at night, Milwaukee DPW regularly receives requests for improving lighting along streets and trails. I imagine this will continue to be a priority as we implement our Complete Streets policy.

Related News

© 2025 Smart Growth America. All rights reserved

Site By3Lane Marketing