News

By Admin, June 3, 2010

No community wants to have polluted, vacant land within its borders.

Families don't want to walk past the old abandoned steel factory every day, it's a drag on city tax coffers when land is underutilized, and it's a shame when new growth is booming on a city's sprawling edge at the same time that vacant land goes begging near the center of town due to past pollution on the site.

Since 1995, the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) Brownfields Program has helped communities across the country assess and clean up thousands of those contaminated, vacant properties known collectively as "brownfields," leveraging more than $14 billion in public and private investment and contributing to the creation of more than 60,000 jobs in the process.

It's a good story, but it's a process that needs to be streamlined, expanded, and made more predictable.

|  |

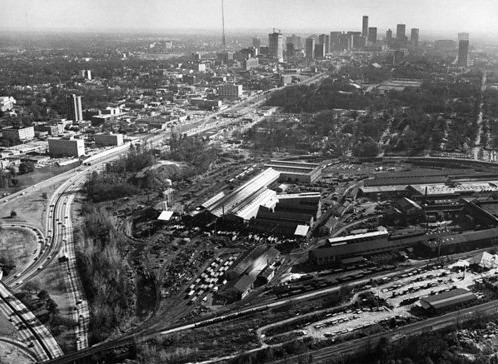

| Atlantic Steel in 1971, originally uploaded by whiteknuckled. | 17 1/2 Street, originally uploaded by TheOtter. |

| One of the most well-known brownfield success stories, the old Atlantic Steel site in Atlanta, Georgia (shown above in 1971) was cleaned up and restored to productive use. Today, the site is occupied by office space, an outdoor mall and shops, and residential areas near Midtown Atlanta on the same site that sat vacant and polluted for several decades. The site was developed in a smart walkable fashion near the city center, resulting in a place where residents drive 2/3 less than their fellow Atlantans. | |

Over the last several months, Smart Growth America has been working as part of the National Brownfields Coalition to help reauthorize this vital program, with a series of amendments to improve it. Last week, Congressmen Pallone (D-NJ) and Sestak (D-PA) introduced a bill (H.R. 5310) that would do just that. Among the important changes that the bill would make to the EPA Brownfields Program are these three things:

(1) This bill would make nonprofits eligible for a broader array of EPA brownfields funding.

Nonprofits are often positioned to be key players in revitalizing communities through brownfield redevelopment. They have the long-term vision and active presence necessary to guide revitalization efforts that often last well beyond the limits of an election cycle, as well as the specialized knowledge to act as catalysts, coordinating brownfield activities for community-based organizations that might otherwise pass up these sites, and helping to ensure that redevelopment truly involves and serves communities. However, under current law, nonprofits are ineligible to receive federal funding through several of EPA’s grant programs, limiting their ability to conduct site assessment and planning activities or administer loan funds.

(2) This bill would create a multi-purpose grant program that would provide funding for communities to inventory, characterize, assess, plan and cleanup brownfields through a single streamlined application process.

Under the current brownfields law, grant applicants must apply separately for site assessment grants and cleanup grants, even for the same site. They can only apply for a cleanup grant once an assessment has been completed and they can only apply once a year for federal assistance. This unnecessary and onerous restriction means that communities undertaking multiple stages of cleanup and redevelopment face uncertainty, extended timelines and a stymied ability to plan for the future.

Uncertainty is the last thing that a potential developer of a formerly polluted site wants to hear, and difficulties in the process are why many developers choose to go build on the fringe where regulations are few and the process is more predictable.

(3) This bill would provide funding to prepare sites for sustainable uses, providing a win-win for smart redevelopment.

Brownfield sites often represent ideal locations for “green” projects – mixed use development near transit, wind farms and solar panels, green infrastructure, and more. (Consider the case of Atlantic Station in the photographs above.) The program also clarifies liability issues, provides resources for localities’ brownfields-related administrative costs, and raises funding caps associated with the program.

You can read the full bill here (pdf). Contact your Representative today to ask him or her to cosponsor H.R. 5310!

Related News

© 2025 Smart Growth America. All rights reserved

Site By3Lane Marketing