News

By Smart Growth America, September 8, 2017

What begun as a sort of arts-driven guerilla marketing campaign for the fictional return of a historic streetcar in the border communities of El Paso, TX and Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, is becoming a reality, a demonstration of the power of art to capture the imagination of a community and help them look at old problems in different ways and imagine creative solutions.

This story is part of arts and culture month at Smart Growth America, where we’re telling a handful of stories about how arts and culture are essential to building better transportation projects and stronger communities. It's adapted from a longer case study that will be featured in Transportation for America and ArtPlace America’s upcoming field scan on arts, culture and transportation.

Unlike San Diego, CA and Tijuana, Mexico, which are separated by 20 miles, El Paso, TX and Ciudad Juárez, Mexico sit immediately adjacent to one another, separated only by the width of the Rio Grande River and the international border between the United States and Mexico. Until 1846, El Paso was in fact part of Juárez and Mexico, and the two independent cities today form the world’s largest binational metroplex, with thousands of daily crossings by foot, car, and bus; billions of dollars of trade; and five border crossings connecting the two cities and region. For generations, residents on both sides of the border have crossed frequently for work, school, recreation, and to visit family; more than 80 percent of El Pasoans identify as Latinx.

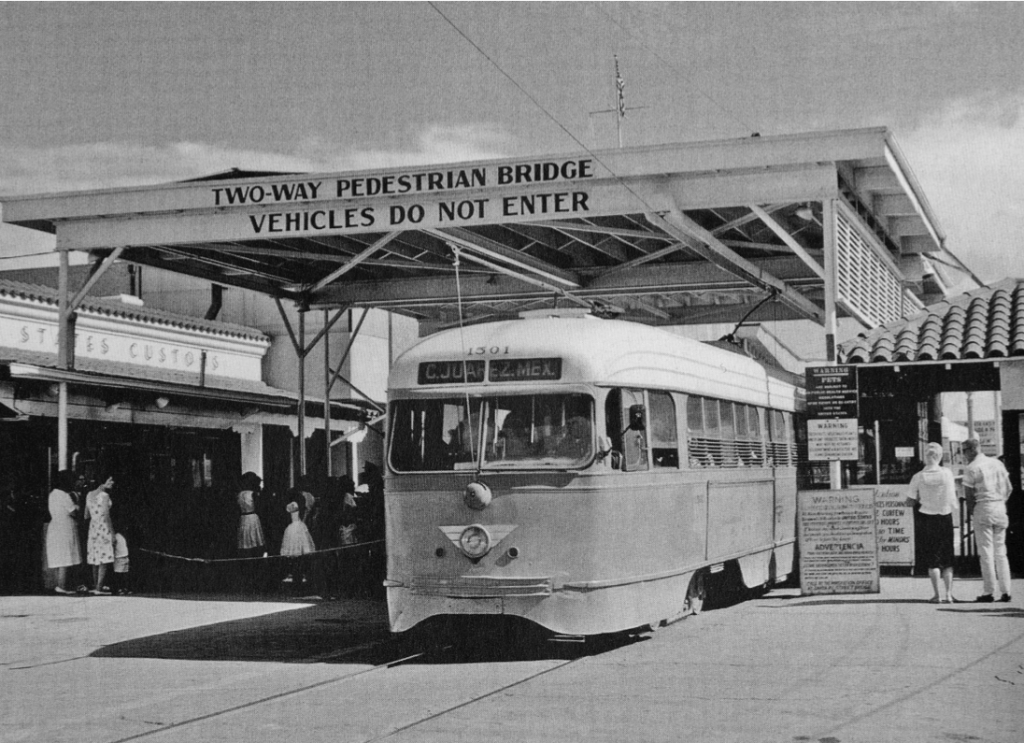

Until it was closed down in 1974, these border crossings were facilitated in part by an international streetcar system that connected the downtowns of both cities. As in many American cities, the streetcar system ran President’s Conference Committee (PCC) streetcars, with a sleek Art Deco design that was introduced after the Great Depression to lure new car owners back onto public transportation.

The iconic streetcars and stories of their transnational past served as the inspiration for Peter Svarzbein’s Masters of Fine Arts thesis project at New York’s School for Visual Arts. In 2012 Mr. Svarzbein, a native of El Paso, created the El Paso Transnational Trolley, which could be described as part performance art, part guerrilla marketing, part visual art installation, and part fake advertising campaign. The project began with a series of wheatpaste posters advertising the return of the El Paso-Juárez streetcar, and continued with the deployment of Alex the Trolley Conductor, a new mascot and spokesperson for the alleged new service. Alex appeared at Comic Cons, public parks, conferences, and other public spaces to promote the return of the streetcar, while additional advertisements appeared across El Paso, sparking curiosity and excitement for the assumed real project.

Eventually, Svarzbein admitted that the project was a graduate thesis masquerading as a streetcar launch, but rather than graduating and moving on, he decided to move back home to El Paso.

When Svarzbein learned that the City of El Paso planned to sell the historic PCC streetcars, he lobbied the city to cancel the sale, and instead return the streetcars to the streets of El Paso. Thanks to the region’s dry climate, the streetcars have remained in relatively good shape for the past four decades even though they’ve been stored in the open desert at the edge of El Paso.

After gathering thousands of signatures in support of the project and with the strong backing of the City of El Paso and Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT) Commissioner Ted Haughton, the El Paso trolley won a $97 million grant from TxDOT. It is now slated to begin service in El Paso in 2018. The third phase of the project will include a connection to the Medical Center of the Americas, while the second will include the much anticipated transnational connection to Juárez.

In one of the most surprising twists in this long tale, shortly after this funding was awarded, Svarzbein rode the wave of public support for the once-fictional project to win a seat on El Paso’s City Council.

Svarzbein’s approach as an artist transformed the discussion. The project's website quotes artist Guillermo Goméz-Peña: “An artist thinks differently, imagines a better world, and tries to render it in surprising ways. And this becomes a way for his/her audiences to experience the possibilities of freedom that they can’t find in reality.”

Clearly, Svarzbein credits his creative campaign with helping to get the project off the ground and building the community support needed to win funding, claiming that "there is a sort of responsibility that artists have to imagine and speak about a future that may not be able to be voiced by a large amount of people in the present. I felt that sort of responsibility. If I couldn't change the debate, at least I could sort of write a love letter to the place that raised me."

This story is another example of how transportation professionals are exploring new, creative, and contextually-specific approaches to planning and building transportation projects. They are collaborating with artists and the community in new ways to transform transportation systems into powerful tools to help people access opportunity, drive economic development, improve health and safety, and build the civic and social capital that binds communities together.

This project is just one of the many case studies that will be featured in our Transportation for America program's upcoming field scan on arts, culture and transportation, commissioned by ArtPlace America. The field scan is intended to examine the ways in which arts and culture are helping to solve transportation challenges while engaging the community in a more inclusive process.

Stay tuned for more about arts and culture during the entire month of September.

Related News

© 2026 Smart Growth America. All rights reserved

Site By3Lane Marketing