News

By Sean Doyle, March 7, 2019

This is the fourth post in a short series about states that are finding success through what's known as practical solutions, a way for transportation departments to meet changing demands and plan, design, construct, operate, and maintain context-sensitive transportation networks that work for all modes of travel. Read the first, second, and third posts. Read the fifth post here.

This is the fourth post in a short series about states that are finding success through what's known as practical solutions, a way for transportation departments to meet changing demands and plan, design, construct, operate, and maintain context-sensitive transportation networks that work for all modes of travel. Read the first, second, and third posts. Read the fifth post here.

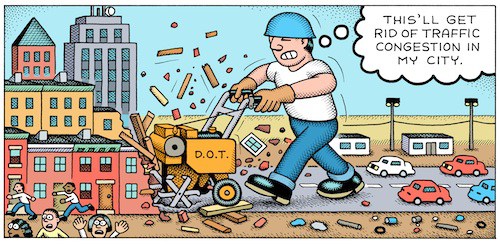

As we covered in the previous post, to better consider all of the users of the transportation system, state DOTs need to update the embedded culture, practices and processes that affect projects long before a shovel is ever put in the ground. But making these upstream changes will only get you so far and the assumptions used during project design and project selection are a major obstacle to change.

As Brian Tracy famously said, "incorrect assumptions lie at the root of every failure." And they have to be brought to the surface and addressed head-on. First is the biggest assumption of them all: That the basis of most roadway design, level-of-service, is an adequate measure of transportation performance.

Reevaluating level-of-service

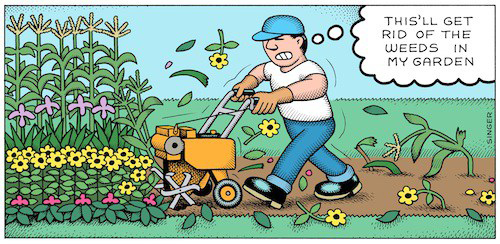

Level-of-service (LOS) has been the dominant performance measure for roadway design, and continues to drive transportation agencies toward overbuilt, expensive, car-oriented highways and sprawling development. It's a blunt measure of traffic delay that assigns a letter grade based on the number of seconds vehicles (and only vehicles, not people) have to wait to go through a corridor or an intersection during a particular hour. An 'A' grade means free flowing traffic , an 'F' means a forced or breakdown in traffic flow. DOTs will never be able to shift practices away from over-designing roadways unless they take steps to change expectations around LOS. Quite simply, LOS is the elephant in the room.

There are three main options to deal with this elephant.

First, state DOTs can relax their commitment to using LOS. It may often be okay to accept some vehicle delay, especially if that fits with community goals for a walkable corridor or in an instance where LOS is only degraded for a short period of time each day (like evening rush hour) but is otherwise acceptable.

The second option would be to adjust the weight of LOS relative to other measures like safety or accessibility to paint a more accurate picture of the need for projects beyond "always move the cars fast." LOS often gets the most weight and as a result is really the only factor that matters.

The final option, and the most ambitious one, is to replace LOS with a different measure altogether and flip the existing paradigm on its head. Instead of measuring the delay cars experience (regardless of journey length or overall time), using vehicle miles traveled (VMT) instead measures how far people are traveling. States can then set goals to reduce driving in order to improve air quality or address inequities in the transportation system. In California, state law (SB743) has required state agencies and municipalities to stop using LOS in an effort to reduce greenhouse gas emissions; VMT has been the prevailing replacement. You can read more in detail about this from T4America.

LOS is a relic of the 1960s when we were setting standards for a new national highway system. It makes sense for limited access highways. However, it is now applied rather thoughtlessly to all roads, even neighborhood roads, where the priority is not (or should not be) free-flowing, high-speed vehicle travel. The priority instead may be quality of life or walkability or safety.

LOS is a relic of the 1960s when we were setting standards for a new national highway system. It makes sense for limited access highways. However, it is now applied rather thoughtlessly to all roads, even neighborhood roads, where the priority is not (or should not be) free-flowing, high-speed vehicle travel. The priority instead may be quality of life or walkability or safety.

Assuming that LOS is an effective measure for the entire transportation system is just one of many assumption state DOTs need to reevaluate.

Addressing assumptions and expanding flexibility

To anticipate future needs, DOTs typically attempt to forecast the future and anticipate what might be necessary in 20 years, often resulting in large, expensive projects that are not yet necessary—and may never be. And excess road capacity is known to induce more demand, creating a vicious cycle. While the intention is noble, it is impossible to forecast traffic conditions 20 years out and existing models assume traffic growth is inevitable (an outdated assumption in and of itself).

Other assumptions are based on the perceived need to build to the "highest level" of road design, design that is largely based on highways built in rural settings: straight, wide lanes and spacious shoulders. This kind of design is rarely appropriate beyond rural settings or limited access highways, yet state DOTs still build roads as if it were. Instead, cost-effective design that supports local economic activity and all kinds of travelers should be encouraged.

However, such designs often require a "design exception" or "waiver" because they deviate from the established highway-style design standards. Including commonly requested design exceptions into the DOT standards themselves is one way to encourage their application. Changes in terminology to avoid terms like "exceptions" or "waivers" that imply that something is amiss or unusual can help too. States can also make the process easier or less intimidating by offering guidance on common circumstances where "appropriate design" might be warranted and what justification might be needed.

And finally, the model that states use to determine the level of traffic roads should be built to accommodate (known as the 4-step model) is a blunt tool that should be reassessed. Among its flaws, it doesn't capture shorter trips, so it leaves out bicyclists and pedestrians. It also contains a lot of baked-in assumptions—like consistent, high growth in population and overall travel, and that most (if not all) trips will be in a car—that are often wrong and fail to take into account changing development or personal preferences that affect where people live and travel to.

In other words, this model will assume you are going to drive four blocks from work to lunch, whether you are in a sprawling area that is dangerous for pedestrians or a busy, easily walkable downtown where parking is in short supply and restaurants are all around. This blunt model is what we use as the basis for designing hundreds of billions of dollars of projects each year. For a more in-depth look at the 4-step model and potential fixes, see the memo.

Many of these decades-old assumptions were designed specifically for highways but have been applied to all roads, and haven't been updated to reflect the new responsibilities DOTs have or the new challenges states face today. As we'll explain in our next post, updating or eliminating these assumptions in agency work can help pave the way to projects that better reflect their context and community needs.

Read the fifth post in this series: If that road feels out of place, that’s probably because it is >>

Related News

© 2026 Smart Growth America. All rights reserved

Site By3Lane Marketing